Leaving New Orleans • by Bonnie Noonan

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA • AUGUST 25, 2005.

9:30 P.M.

I’m

on the City

Park side of Bayou St. John, walking my landlord's new beagle. She’s full grown,

but skittish. We’ve become fond of each other. She had come down to my apartment

for a visit again. We were lying in the bed reading Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink

when I felt myself nodding off. “Let’s go out for one last walk,” I said, “before

I bring you back upstairs. I’ve got to get up early for school tomorrow.”

I’ve just spent my fourth day teaching as a full-fledged tenure-track professor.

I’ve come late to this career, I know, but I’m making up for my profligate, rat-panic

youth and actually feel somewhat satisfied. Here come two young women. They’re

walking what looks to be a collie.

“Sorry,” I say, as the beagle bounds back and forth between me and them, pulling

hard on her leash. “She doesn’t know whether to romp or flee. She was rescued

off the interstate not too long ago.”

“I understand,” one of them says. “Ours was rescued from….”

Then their dog jumps up as the beagle yanks back (strong little bitch) and I’m

on my way down. This is embarrassing. How am I going to regain my (admittedly

middle-aged) savoir-faire after this graceless move? I hit the grass. I hear

a peculiar crack. Even though I’ve never broken a bone in my life, I know immediately

what has happened. I say rather calmly and matter-of-factly to the young women

(what else can I do but admit it?): "I just broke my arm."

They are apologetic (they think it was their dog that caused me to fall, not

realizing that the beagle — now extricated from her collar and gallivanting wildly

— is the true culprit). They are extremely solicitous, as if I could be a mother

to either one of them curled in astonishing pain, lying in dirt.

“I’m a nurse,” one of them says. “Do you want me to look at it?”

“Don’t touch me. No, please, don’t even come close.”

Now picture me stretched out on some type of gurney (my best friend Leslie and

her girlfriend Pam have taken me to the bright Mercy Hospital Emergency Room).

A young orthopedist is burying a burning hypodermic full of what I pray is some

type of numbing agent into my wrist, moving it here, moving it there, I think

he’s sticking it into the bone. Hear me involuntarily calling out for Jesus,

no joke.

Now I’m back home, sedated (a “chill pill” they called it). Leslie tells me she’ll

take my prescription to the Rite-Aid tomorrow…even though the arm I have broken

is my left. See? Not my Rite? Hahaha! Now I’m stupid, too. No really, I’m left

handed. This is going to be difficult. My arm is encased right up to the elbow

in a heavy white plaster cast. (It’s temporary. I’m supposed to see a real orthopedist

in six days to get a lightweight, tight-fitting fiberglass one.) My wrist is

bent into an awkward, extended position (“Traction,” the young orthopedist said)

and I can’t move my thumb.

“Do you know a hurricane might be going into the Gulf?” Leslie says.

“Why did this happen to me?” I ask her. I thought my life was on track.

STILL IN NEW ORLEANS. SUNDAY, AUGUST 28. 4 A.M.

I’m inside the living room

of my low-ceilinged, one-bedroom, Mid-City apartment, shuttered by trees and

bushes from the street outside. My little nest, I call it, my tree house, even

though I’m on the ground floor. I’m up to check the latest coordinates of Hurricane

Katrina. She should have turned to the east (sorry, Gulfport) during the night

and then weakened (they always do). The TV’s been on all night. The Weather Channel

— just in case. I haven’t even had coffee yet. Sleep shirt, underwear, hair like

a rooster. The new coordinates tell me there’s been no change in course, no decrease

in intensity. Katrina’s a strong Category Four, headed straight for us.

The neighborhood is quiet. Leslie and Pam have already gone. Betty across the

street has left with her mother (her mother has Alzheimer’s). My next-door neighbor

Mark, a no-nonsense Navy guy, tossed a pup tent and sleeping bag in the back

of his pick-up and drove on out. My landlord left the night before with his anxious

wife, two-year-old twins, very old cat, and Lucy (the beagle that broke my arm)

to push through 280 miles of stop-and-go, we’re-not-prepared-to-evacuate traffic

and stay with his mother-in-law. Like the others, they urged me to come with.

“That’s alright,” I told him.

“We’ll leave the upstairs door open for you,” he said.

“Do you have an attic access?”

“Yeah, it’s in the hallway by the boys’ room. Want me to show you how to work

it?”

“Nah, we had one when I was a kid. Just pull it down and climb up.”

“Don’t forget, the axe is over in the corner.”

“I doubt the water’ll come that high. And Rob, if we have to replace the carpet,

let’s do tile, okay?” “I already thought of that. Help yourself to whatever’s

in the fridge.”

Now here I am, staring at the image on the television screen. Katrina’s red,

her eye as big as a silver dollar. Outer bands are a quarter inch from the Louisiana

coast, half an inch from Lake Pontchartrain. I get a sudden sick feeling in the

pit of my stomach. Blink. Should I try to save my record albums (Ultimate Spinach,

Joan Armatrading, Laura Nyro)? My 45s (Etta James, Mary Wells, Irma Thomas, very

early Beatles)? They’re on a bottom shelf. I can’t lift them. My broken arm’s

too painful, too fresh.

I pick up my laptop, but I won’t have time to work. Antigone can wait. I’ll be

home in three days. I pick up Mama’s bible. Should I bring it? I think about

some of the passages she underlined — “I can do all things through Him who strengthens

me,” “Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” I pick it up,

feel foolish, put it down. I pull on grey gym shorts, my short-sleeved nylon

Jazz Fest shirt (the one with the accordions on it), grab my pain pills, and

open the suitcase.

LEAVING MID-CITY. STILL SUNDAY, AUGUST 28. 6 A.M.

I’m on my way to Lakeview

to pick up my good friend Manina, another die-hard New Orleanian who never leaves

either. The streets are empty in the early dawn. Mine is the only car on Wisner

Boulevard — the rippling bayou on one side; lush, green City Park on the other.

Manina’s living room light is on. She answers the door in her nightgown. The

TV’s on. She looks resigned. She fixes me a cup of dark coffee with chicory.

I sit in her easy chair and focus on our favorite local weatherman, Bob Breck,

who will disagree with official hurricane center projections and even the mayor’s

orders to evacuate if he thinks he’s right — and he usually is. He’s frazzled.

“Those people who don’t leave the Mississippi Gulf Coast,” he says, “are going

to be dead.”

I tell Manina to hurry. She tells me I’m rushing her. “Yes,” I say, “I am.” Her

block tends to flood even if we just have a hard rain, so she leaves to park

her car over by the old civil defense fallout shelter. I’ve been instructed to

sit quietly and pretend I’m not in the house so her cats will be approachable

when she drags out the cat carriers. She raised Pearl (brilliant white) from

a homeless street kitten and eventually tamed a pregnant and feral Camellia Rose,

who now rarely leaves the house.

When Camellia sees the carrier, she races to

a shelf in the walk-in closet. “I’m not gonna take her,” Manina says. I think

this is probably a good idea. She’s kneeling down petting Pearl and then suddenly

says, “I’m not taking him either.” I’m surprised by this statement because Pearl

is such, as Manina refers to him, “a titty baby” (he sleeps in her arms every

night), but I don’t say anything. Maybe I should have.

We place bowls of food and water on the floor in the kitchen, the dining room,

the living room, Manina’s bedroom, and the guest bedroom, where Pearl is sitting

on the desk, staring out the window, and make sure all the inside doors are propped

open. We check outside to make sure all the garbage cans and flowerpots have

been put away and the chairs have been brought in off the front porch. We put

Manina’s suitcase next to mine in the trunk of my Saturn (thank goodness I filled

up with gas the day before) and make sure we each have a bottle of water.

“Anything else?”

One last look at the house. “I think that’s it.”

We decide to drive north (traffic’s at a standstill going west) and set out

on a quiet highway. This is Manina: “Do you think we should have taken two cars?”

“Do you think I should go back and try to catch the cats?” “Are you sure we can’t

just stay home?” “Do you have a map?” This is me: “No.”

I-59 HEADING NORTH

Manina holds the wheel while I take a pain pill. I sit quietly while she cries

into her cell phone, trying to convince her friend Pat to leave Bay St. Louis;

another friend just diagnosed with brain cancer to get out of the Hyatt. Suddenly

we realize we’re in contraflow. We stop at rest stops and pee in the woods (along

with everybody else).

Why wait in line forty-five minutes for a toilet that’s

probably already stopped up?

When we get to Jackson, I want to stop, look for a motel room, lie down. Manina

reminds me that 1) there are no motel rooms to get and 2) Katrina is coming up

after us. We stop for coffee, find out Katrina’s been a Category Five since 7

a.m. No change in course. Let’s aim for Memphis.

A hundred and fifty miles later, we stop at a string of roadside motels. Not

a room. Not until at least 100 miles past Memphis. But there is some sort of

a slot, a desk clerk tells us, at a fishing lodge some twenty miles outside of

a town we’ve never heard of. Only one double bed. $30. Right next to a lake.

Whatever. We’ll take it.

I’d like to say the room we found was sort of a partitioned-off area in what

looked like a double-wide trailer, except for the fact that it actually was a

partitioned-off area in what actually was a double-wide trailer. Careful not

to inhale lest we choked on a veil of mosquitoes, we were quite disappointed

when we found that the particular partitioned-off area we had reserved for $30

was soaked in two inches of water.

“Sorry, water heater must have broke. We’ll get the fan. You want to get something

to eat? We have a restaurant.” We order BLTs. Figure that’s the safest thing

on the menu (which, by the way, has a notice that says “you catch it, we’ll cook

it”). Manina’s crying again. Just as a very kind woman offers us her shed (but

warns us there might be rats), an older couple decides to abandon their (damp)

slot next to our flooded one. “Can’t take it,” they tell us, “we’re gonna keep

driving.” The room has two double beds, the proprietress says, but we can have

it for the same price.

There’s only one light bulb hanging down from the ceiling, but it works. I don’t

know what kind of bugs those are coming out of the corner of the shower stall.

They’ve left what looks like it might be a sawdust trail.

“Maybe they’re weevils,” Manina says.

“Just pretend you don’t see them,” I tell her.

We’re exhausted and dirty. Surprise. There’s no hot water in the shower. I hear

Manina sobbing. She’s thrown herself down on one of the beds, the one farther

from the broken air-conditioner. “It’ll be over soon, Neen,” I reassure her.

“We can leave in the morning and get the jump on the traffic heading back into

the city.”

“Do you think I left the cats enough food?”

“More than enough, Neen.”

“They probably already ate all of it.”

“Then they’ll be angry and fat.”

“Little shits.”

“I don’t trust this mattress,” I say. “I’m gonna sleep on top of the spread.”

“You’re gonna be cold that air-conditioner is blowing so hard.”

“Maybe we can open the door…”

“…and breathe some mosquitoes.”

“Good thing there’s no windows.”

“Maybe we should call room service.” Finally we’re laughing.

AT THE FISHING CAMP. MONDAY, AUGUST 29. 7 A.M.

Manina and I are having coffee and eggs. Katrina’s making landfall on the Louisiana

coast. Manina thinks the fishing camp is going to flood. Let’s go to Arkansas.

Maybe Little Rock. We can stop at the Clinton Library. Hahaha. Then we can go

home.

A lady tells us at a rest stop that we should go through Hot Springs, the baths

are really nice. Another lady and her sister tell us they’re going to Dollywood.

May as well, they say, they’re already up here by Tennessee. “How can they think

about taking a vacation?” Manina asks, exasperated.

The folks at the Arkansas Welcome Center tell us there’s a room — not in Little

Rock, there’s nothing in Little Rock — but in a small town called Forrest City.

It’s in what used to be a Budget Inn, but got downgraded. Manina finds a discount

coupon in one of the welcome center brochures. It’s expired, but they give it

to us anyway.

We open the door to paisley bedspreads, patterned indoor/outdoor carpeting, a

lamp by each bed, cable (free HBO!), a clean bathroom (no weevils!). We unpack

our suitcases, put out our toiletries, turn on CNN, and prepare to be bored.

It looks like the storm turned to the east at the last minute. The eye hit Slidell.

Good news for New Orleans. Bad news for my stubborn-ass, dope-smoking ex-husband

Milton, who refused to evacuate. I had called him from the fishing camp to tell

him I was all right, and he was so freakin’ stoned he kept hanging up the phone

and calling me back. Then one of his friends called me.

“Milton says he’s sorry.”

“Oh, Jesus, lemme talk to him.”

“Hello?” he says, then he hangs up the phone. Calls me back, laughing hysterically.

“Milton. Enough. I’ll talk to you tomorrow.” Last words I said to him.

Now I can’t get through.

“I shoulda picked him up,” I tell Manina.

“He wouldn’t have come.”

“Still.”

“I should have taken the cats,” Manina says.

“They’d have hated it. Cats love to be in their own home.”

“They’d have been less trouble than Milton.”

Now here’s some CNN fool with a microphone on downtown Canal Street. Palm trees

that the city spent who knows how much money on to plant in concrete are all

blown flat over. “The storm is just grazing the city now, but I’m going to see

just how hard that wind is blowing,” the fool announces. He crouches down like

he’s in Iraq and runs out behind a mailbox. “I’m relatively safe here,” he says.

A piece of pipe or chrome or something clangs by and gets caught up on the mailbox.

Fool grabs it, holds it up triumphant.

Now a skinny white-haired man is driving into the water that’s covering the I-10

by the West End underpass (it always floods). What was he thinking? An excited

reporter pulls him out of the driver-side window. His cameraman films the whole

daring rescue.

“What were you thinking?” the newsman asks, pointing a microphone at the poor

fellow’s face. “I was going to my mama’s house,” he says, bewildered.

Here come a string of commercials. Now the video of the bewildered man driving

straight into the water again, his trunk bobbing up as the car noses into the

flood waters. “What were you thinking?” the newsman asks again.

“That poor man,” Manina says, “he’s gonna have to see this over and over for

the rest of his life. Every time there’s a hurricane in the Gulf. Every time

there’s a heavy rain in Lakeview.” She decides to go for a walk.

I’m aggravated with myself. I feel like I overreacted. I dragged Manina out of

her quiet house at six o’clock in the morning, made her cry, drove a million

useless miles, and all for another New Orleans shoo-shoo. I turn off the TV.

Pick up Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point.

Manina comes back. “The levees are breaching,” she says, her face ashen.

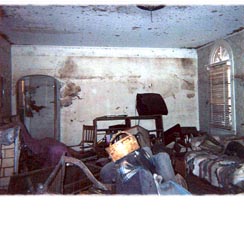

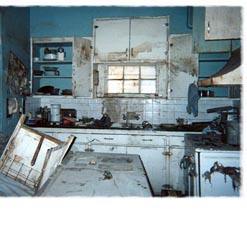

![]()

Bonnie Noonan, proud to be a native New Orleanian,

is an Assistant Professor of English and Director of Composition at Xavier University

of Louisiana. Her article "When Life Gives You Lemons: Katrina as Subject" was

published in the Fall 2007 issue of the South Central Review.

She is also the

author of the book Women Scientists In Fifties Science Fiction Films.

![]()